Three Purposes for a Lead Time Distribution Chart

- Fernando Cuenca

- Dec 3, 2024

- 5 min read

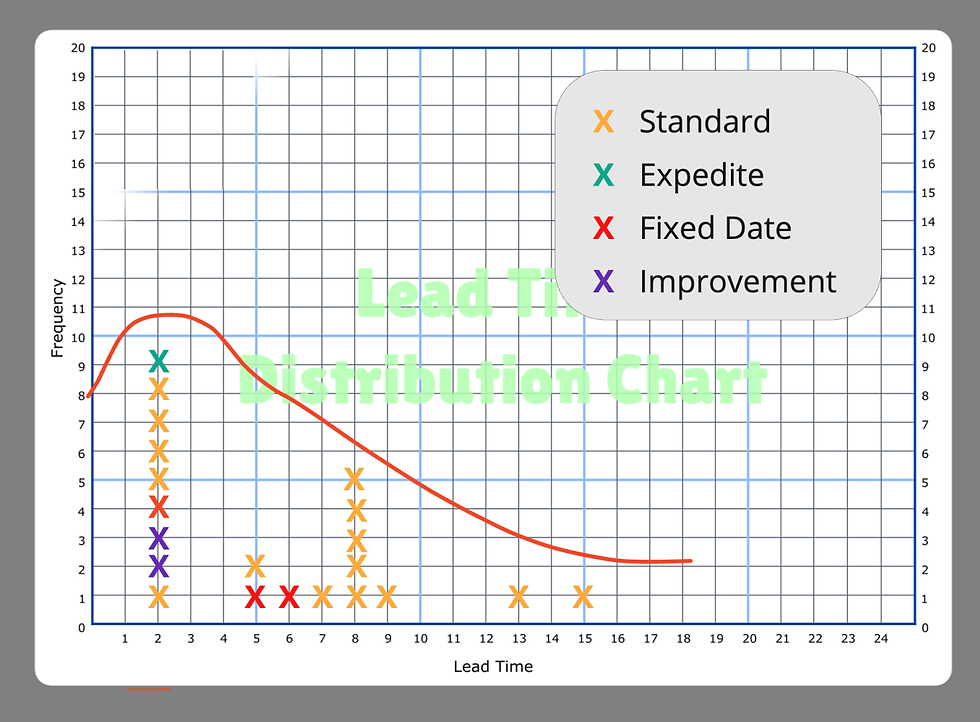

Let's look at a Lead Time Distribution chart:

Each X represents a delivered item, and its position respect to the horizontal axis represents the time it took to get it delivered (in days), known as its "Lead Time" (LT).

A question that people often ask when shown this chart is: "OK, what do I do with this information?"

A first approach to an answer would be that a LT chart is descriptive: it tells you something about your process' predictability (by observing the spread and distribution of the Xs) and speed (by looking at things like the position of the tail, and the height of the hump.) If you also add a "customer fitness threshold" line to it, it can also help answer questions like "how well are we doing?" and "how much do we need to improve?". I've covered this topic in an earlier article.

A LT chart can also be predictive. When you're starting work on a new item (or considering if you should do it now or later), it can help answer a question like: "how long is this likely to take?". There are, of course, several aspects that need to be considered when using a LT chart in this manner (such as the number of data points available, reference periods and whether the system is trending or stable, understanding of variation, and some others), but it can definitely help transitioning from deterministic views to probabilistic thinking.

But what most people really hope for, especially when introducing the practice of tracking and charting Lead Time, is for these charts to be "actionable": they mostly already know that their process needs to be better, but the big question is: "how do we do that?"

LT charts can be "actionable", but only indirectly: by itself it won't answer the question of what/how to improve; for that we will need to investigate and determine why individual items landed where they did on the chart. But the LT chart can guide your efforts by telling you which items to focus on first.

One obvious starting point is the items that fall in the tail. You will probably discover that they were exposed to risks that can result in significant delay, and that if you find ways to mitigate (or eliminate) that risk, that will improve the delivery of many other items that have the same risk exposure. I described the idea in an earlier article.

Another clue can be usually found by identifying work of different nature in the chart, and observing where those items show up.

The following chart is the same that was shown above, but colour-coded to show items that were somehow "different". In this case, the criteria for "different" is "class of service", but you can (and probably should) use some other classification criteria, such as "work item type", "requesting customer", etc.

As a reminder, "class of service" refers to the "treatment" that was given to an item: the set of rules (or "policies") that were followed (either explicitly, o most often, implicitly) to make day-to-day decisions about how to work on this particular item. Class of Service It usually refers to things like priority, or urgency, but it can also be related to other attributes of work, such as quality.

In general terms, what we're looking for is patterns. In this example, it's quite obvious that the non-standard items (colour other than orange) all appear to the left of the distribution; that is, they avoid the tail. That means that, somehow, they tend to be done faster than the standard items. If we can figure out what's the reason for that, we might learn something about our system of work that could be applied to make it better overall.

It's of no surprise that Expedite items (dark green) appear in the "fast" zone of the distribution. After all, Expedite normally means "drop everything and focus on this", which normally results on items jumping ahead of queues, sidestepping bureaucracy, being "swarmed" on, and other measures that help avoid most delays.

Similarly, tickets with a fixed date deadline are unsurprisingly in the same "fast" region. After looking into the practices for this team, let's say we discover that they are usually accepted into the process within a week of when they are due. Then, they are worked on just like Standard items, but the team keeps an eye on the date, and as the deadline approaches, they are given more and more attention, to the point of sometimes being treated just like expedites, to make sure the deadline is always met.

The purple items, however, raise some eyebrows. They represent technical improvements, not direct customer value. When the process was originally defined, they were meant to be used for work that, while important, could always be delayed or postponed to make room for other, more important, customer-value work. It doesn't look like this is what's actually happening.

After asking a few questions, we find that the work is, indeed, technical improvements, but it's introduced when the team has observed an imminent technical threat that needs almost immediate attention, or when the team has observed some other problem mounting that, if left unattended, will create problems for other work in the near future. They respond to this by introducing a technical improvement that is given a relatively high priority. It's never allowed to impede the progress on critical items (like Expedites or Fixed Date items), but it can (and often does) delay Standard items, "within some reasonable limits".

So what's the lesson here?

An initial conclusion we can draw is that, probabilistic delays aside, how long work takes is also dictated by the way we choose to treat it. Differences in intrinsic considerations like "size" and "complexity" will have an effect, but we're not completely at their mercy; decisions we make about treatment of the work (or "class of service") will allow us to manage around those differences and delays, and get work delivered faster, essentially by "borrowing" LT from some items to "give" it to others.

But there's a more general observation we can make.

Teams often follow some implicit rules that result in patterns: we can use the distribution chart to find those patterns and make the rules that produce them more explicit. If those rules are producing different LT results that we find more desirable, perhaps we can apply those rules more deliberately to other items to obtain similar results.

In the example above, the policy that's at play is essentially that there is a class of service that it's "higher than" Standard, but "lower than" Fixed Date and Expedite. The original intention might have been for this items to fall to the bottom of the priority rank and be delayed often (that is, given "Intangible" class of service), but that's not what's happening in practice. The purple items are given slightly more attention than the orange items, while at the same time not blocking them completely (as it is the case with Expedites and Fixed Date item that are getting "too late").

But more importantly, this analysis shows that the team has the "capability" of delivering work at this "faster than Standard" speed. Currently, that capability is used for Improvement work, but with the insights coming from analyzing the LT chart, the team might decide to apply this mode of delivery to some Customer items too, according to some criteria.

Or perhaps they might conclude that this is a deviation from the original intent, and change the way technical improvements are handled, reclaiming some of that capability for Customer items, and thus improving the service in the eyes of their Customers.

Comments